169 “anomalies” discovered at former residential school site in Northern Alberta

KAPAWE’NO FIRST NATION, AB – The initial findings of a ground-penetrating radar search has unveiled the possibility of up to 169 child graves at a former residential school in Northern Alberta.

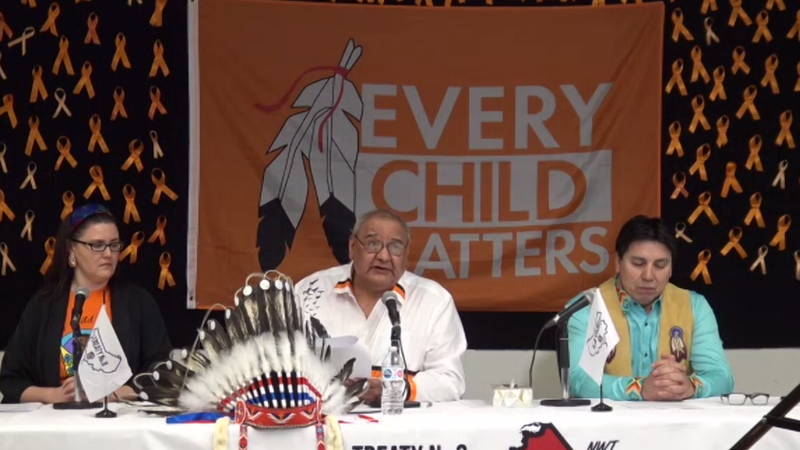

The Kapawe’no First Nation has released the results of phase one of their search into the former St. Bernard Mission, located approximately 151 kilometres southwest of Peace River.

Officials say they found 169 “anomalies” in the one-acre area that was part of the first phase, which would potentially represent children who died at the former residential school.

That includes 115 unmarked graves at the cemetery where other members of the community were buried as well.