Sudan armed raids, bureaucracy hampering life-saving aid, doctor says

OTTAWA — As Canada crafts its response to the crisis in Sudan, a doctor trying to co-ordinate basic medical services after the country’s rapid descent into chaos says bandits and bureaucracy are hampering life-saving aid and leaving children to die.

“The people of Sudan are not getting as much care as they could, because our warehouses are being looted and we don’t have safe access to them,” said Javid Abdelmoneim, a Doctors Without Borders emergency-room physician.

In a recent call from Sudan’s Gedaref state, near the border with Ethiopia, Abdelmoneim said the crisis is unlike ones he’s seen in Syria, Ukraine or Ethiopia, not just because of random violence, but also because of bureaucratic hurdles.

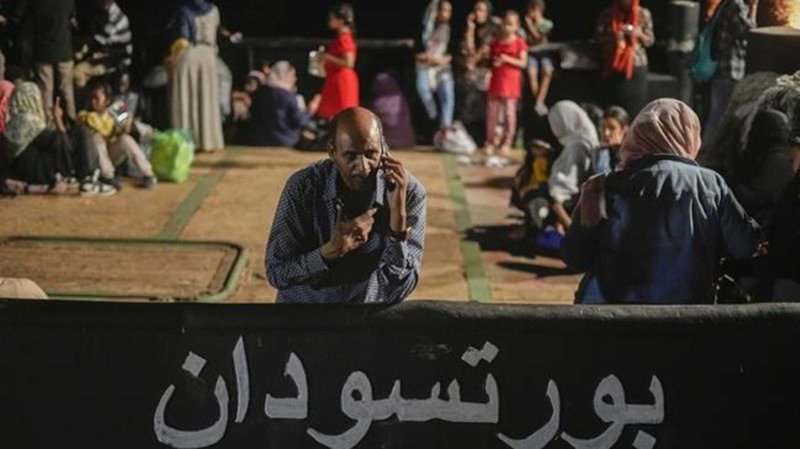

In mid-April, a longstanding feud between the country’s military and its paramilitary force broke out into a turf war in the capital of Khartoum and led to violence across the country of 46 million people.