Ottawa gives Manitoba chiefs money to study reforming child-welfare system

WINNIPEG — Canada’s indigenous affairs minister says Manitoba child welfare should move away from rewarding the apprehension of children to focus more on keeping families together.

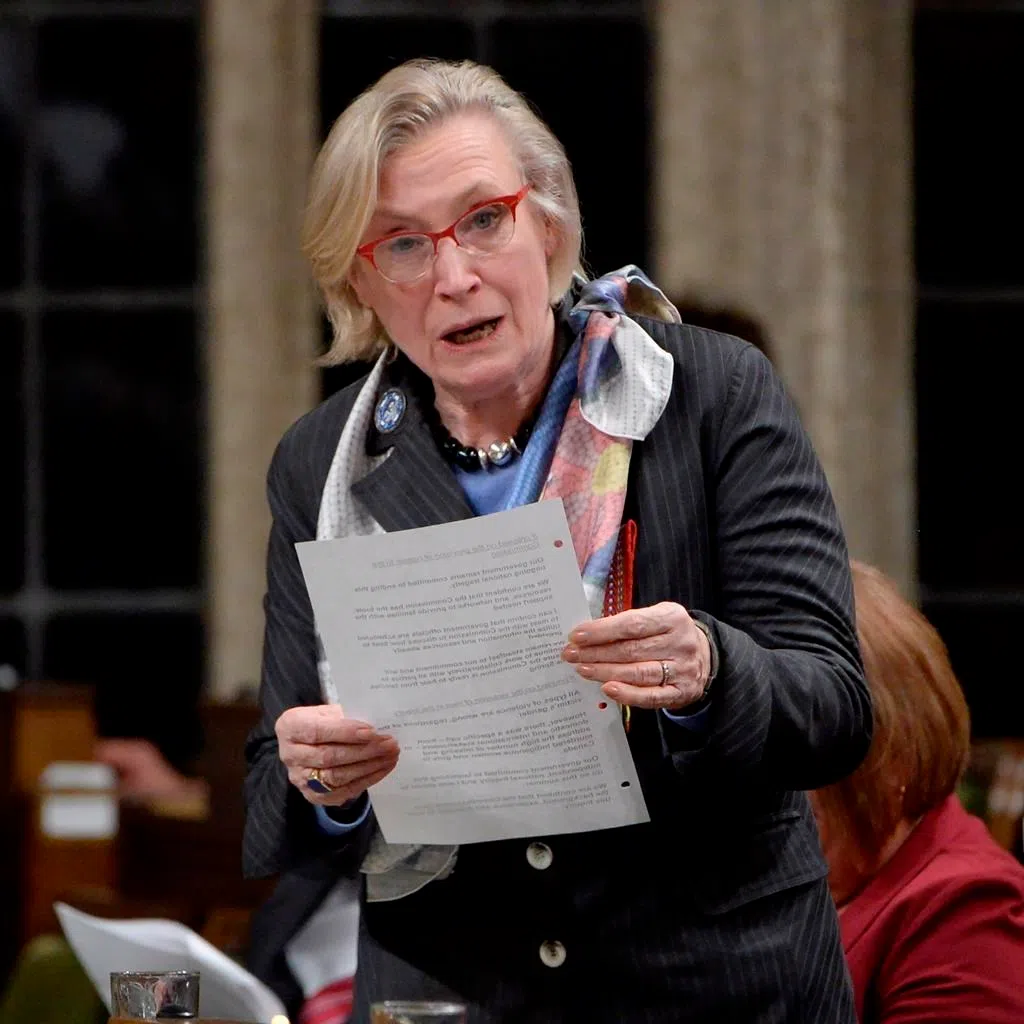

“If agencies get more money because they’ve apprehended more children, and the money is going to lawyers to apprehend more children, that isn’t where we want the money to go,” Carolyn Bennett said Monday after a funding announcement in Winnipeg.

“We want it to go to kids and to keeping families together.”

The federal government is giving the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs $550,000 to consult with First Nations communities across the province on how to reform Child and Family Services.